America’s descent into carnival and spectacle

Native mystery and transcendence displaced by the grotesque infantilism of the permanent now

“The state of society is one in which the members have suffered amputation from the trunk, and strut about so many walking monsters—a good finger, a neck, a stomach, an elbow, but never a man.” – Emerson, The American Scholar, 1837

What has happened to the United States of America? Masculine pronouns aside, Emerson’s nearly 200 year old description of grotesque social dismemberment sounds eerily contemporary.

In addition to increasingly violent political division, all of the nation’s major institutions, from Congress to news media to the presidency, have suffered a historic loss of public confidence, with approval ratings as low as 7% for Congress in 2022. Those who think the country is “on the wrong track” hover between 75-85%.

In the looming $20 billion 2024 election spectacle, forecast to be the most expensive in US history, nearly 60% of voters do not want either of the two leading presidential candidates – Trump nor Biden – to run. Adding to the already divisive turmoil and confusion, there are now said to be 72 “gender identities” besides male and female.

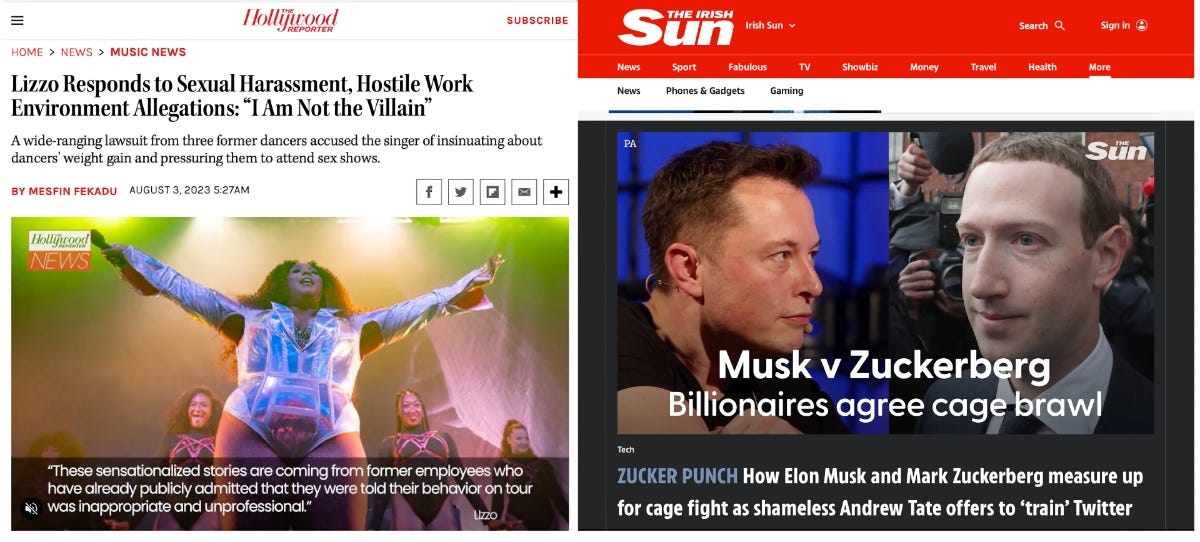

Simultaneously, an annual $2.3 trillion, 24/7 global media entertainment spectacle sells permanent apocalyptic crisis and a reductive, infantilized vision of humanity as a form of environmental pestilence cum reality freak show.

The balance, space and time required for the cultivation of human dignity are not just lost in the onslaught, they are viciously derided. Those who resist the deranged and frenzied imperatives of officially sanctioned nihilistic media narratives are burned at the virtual stake.