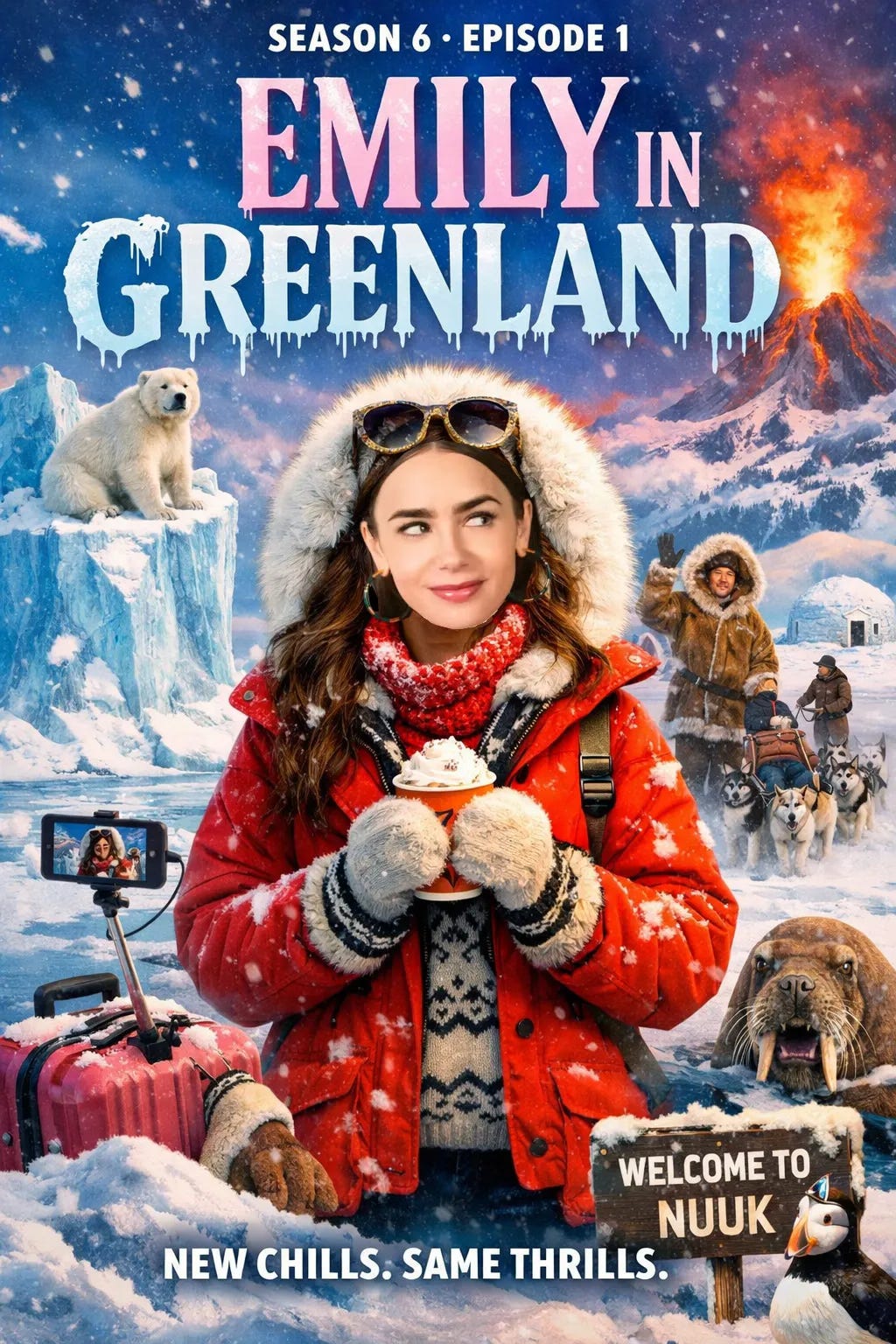

Emily in Greenland, season 6

Emily's cool revolution

Greenland is in the news. In order to stay on top of the cultural zeitgeist, shouldn’t Emily meet an Inuit boyfriend in upcoming Season 6, land a huge PR contract for Agence Grateau with a globally famous Norwegian winter wear brand and move to Nuuk for a few episodes? Maybe she can help Antoine launch a new Maison Lavaux fragrance, Soirée de Mattak, to liven up those long Arctic nights?

A Canadian friend is already sharing story ideas. “Each week, Emily has to outrun a polar bear, deal with vicious seals, etc. One week, while on a hunting trip, she accidentally uncovers a lost village of Viking ancestors. And of course, she will have her regular favorite coffee house in downtown Nuuk. Another week, there will be conflict and romance when some high officials from DC show up, and Em is wooed by somebody close to the US President.”

In a world that seems more chaotic daily, why not give Emily a little artistic license to have some Arctic fun, lightening viewers’ emotional load in the process?

And what if, from her perch atop today’s 24/7 global streaming industry, something more than escapism is already going on with the confection that is Emily?

AMBIENT MEDIA

Writing in the November 2020 New Yorker, Kyle Chayka, author of the column “Infinite Scroll,” says:

By the end of its second episode, I knew that Netflix’s new series “Emily in Paris” was not a lighthearted romantic travelogue but an artifact of contemporary dystopia.

Light hearted Emily as “dystopian”?

Like many other cultural commentators, Chayka has devoted considerable attention to deconstructing Emily in Paris, especially the show’s ubiquitous use of cell phones and social media simulations not just as accessories, but as key elements of story, describing the series as “a shining beacon of banality.”

Springboarding off a famous 1995 essay by architect Rem Koolhaus titled “The Generic City,” Chayka characterizes the show as an example of “ambient media” and shares Koolhaus’s insights on the phenomenon as embodied in modern cities, including Paris as presented in Emily.

"Koolhaas argues that globalization has caused a mass homogenization that leaves modern cities feeling like an airport, “a trance of almost unnoticeable aesthetic experiences.” [T}he “pervasive lack of urgency and insistence acts like a potent drug,” inducing “a hallucination of the normal.” [T]he hypnotic quality of ambient content creates a false sense that whatever it presents is a neutral condition, a common denominator, though it is decidedly not.

Chayka is not alone. Articles and analyses with conflicted titles such as “The ‘Meta-emptiness’ of Emily in Paris” or describing Emily as “Nosferatu in Jimmy Choos” and calling the show “deeply annoying and yet highly watchable” are legion. The show is an avatar of the times and also a ratings juggernaut. Within one week of the Season 5 premiere, Collider gushed:

Emily in Paris has surged back to the top of Netflix’s global charts following the debut of Season 5 on December 18, delivering one of the platform’s most widespread performance spikes of the year. [T]he series secured the No. 1 position across a massive range of territories within days of release, including major markets such as the United States, France, Germany, Italy, Brazil, Canada, the UK, and dozens more.

EMILY’S AMBIENT POLITICS

To the casual viewer, Emily appears to be scrupulously apolitical. Every episode is a lively montage of dishy personal gossip, lover’s trysts, breakups, job crises, a steady thrum of gay and lesbian tinged sub themes and sparkling quick cut video montages of Paris, Rome or Venice, whichever city is serving as backdrop of the moment. Social media popups dot the screen every minute or two carrying messages that serve as the connective tissue between characters and plot lines.

Amidst this constant “communication” among characters, overt discussion of political parties, candidates, elections and even current events are completely absent. In one episode, viewers learn that French First Lady Brigitte Macron follows Emily on Instagram after liking one of her posts about a feminine hygiene product. Em encounters Macron in a restaurant and gets permission to take a selfie with her, which is presented as an unalloyed good. This is as political as things get.

The intentional absence of politics is doubtless part of Emily’s appeal. The New York Times reported in 2023 that 65% of Americans feel “exhausted” when thinking about politics, while only 16% trust the federal government. Emily offers safe haven from toxic political fatigue.

That does not mean that Emily in Paris is missing a political dimension. Its studied apolitical-ness may be the ultimate populist political statement and a key source of the show’s strength among viewers.

THE POWERFUL MARKETING OF LOVING TO HATE EMILY

The common denominator of all marketing and advertising at all times and in all places is the promise of “magical transformation.” Buy our clothes, drive our car, drink our beer or champagne, and your life will be magically transformed.

This promise of magical transformation has a storied pedigree stretching from Marco Polo’s exotic tales of travel over the Silk Road to China, to medieval trade “fayres” (fairs) across Europe to troupes of early American patent medicine peddlers acting as itinerant carnival hucksters.

From the earliest days of the fayre, there were singers, musicians, acrobats, stilt walkers and assorted fools, archery contests and generous sharing of ale, mead or grog. The main goal has always been commerce, but merry making and entertainment were used as advertising to attract and hold a crowd.

In 2026, the fayre continues via globally wired consumer capitalism. The 24/7 virtual celebration of capitalist bounty co-exists with putatively representative democracy only to the extent that such theoretical artifacts as citizens’ political agency do not interfere with marketing. The highest form of citizenship is not consumption itself, and certainly not voting, but a condition of unremitting availability as embodied in social media.

Whether in Paris, Rome or Nuuk, Emily and her cohort of cross generational friends and clients live in an existential condition of permanent availability. In “24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep,” Art critic Jonathan Crary describes a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) project originally designed to develop a “sleepless soldier” that has now morphed into a quest to produce a sleepless consumer who is always available online to consume and produce “content.”

In this new game of “cognitive bio-capitalism,” Emily and Co. are not just ahead of the game, they’re living in the future.

In purely literal terms, Emily is above all else a show about lux marketing of top international brands. Emily’s career at a luxury marketing agency has evolved to the point that scarcely an episode goes by without multiple product placements. In its fifth season, these product placements are so ubiquitous, they’re an integral part of every story. Global brands from Fendi to Miu Miu, Baccarat to Louis Vuitton, and Prada to lowly McDonald’s (dans le style français) are paying up to $1.1 million for a "scripted placement” of a few seconds or minutes.

Rem Koolhaus notes that the branded homogenization of modern cities is punctuated by “periodic stagings of uncertainty,” which in Emily has become the primary plot device. This is the case because the show so perfectly reflects the inner logic of modern capitalism at a historic moment when marketing has overwhelmed politics.

Whether one is “hate watching” Emily or simply enjoying an idealized escape from the daily grind, it is worth noting that the show has its finger on the public pulse in ways most self-proclaimed politicians do not. As media critic Willa Paskin notes, even Emily’s harshest critics inadvertently confirm that the show is “the only piece of pop culture that could break through the relentlessness of the news.”

As for the Season 6 move to Greenland, please be patient and keep your parka ready while my Emily in Greenland pitch works its way through Netflix marketing channels.