César Chávez and the embodiment of hope

The political power of clarity and simplicity

“Once social change begins, it cannot be reversed. You cannot un-educate the person who has learned to read. You cannot humiliate the person who feels pride. You cannot oppress the people who are not afraid anymore.” – César Chávez

The media have made a big deal of President “Joe” Biden placing a bust of César Chávez in the Oval Office. One can only hope that this gesture by a career party apparatchik has some actual meaning beyond empty symbolism, because Chávez’s example as an underdog political organizer is worthy of renewed attention at a time when core democratic liberties are imperiled worldwide.

In their 2020 annual report published March 2021, Freedom House writes:

As a lethal pandemic, economic and physical insecurity, and violent conflict ravaged the world, democracy’s defenders sustained heavy new losses in their struggle against authoritarian foes, shifting the international balance in favor of tyranny.

Of all the “secondary effects” from the Covid pandemic, this loss of liberty may be the most lethal.

LA PAZ

As a guest speaker at a political event many years ago at Nuestra Señora Reina de la Paz, the National César Chávez National Monument, now closed due to Covid except for “virtual tours,” I had a few hours to tour the tiny museum on the grounds, visit the graves of Chávez and his wife Helen Fabela Chávez, and learn about his life story and the history of the United Farm Workers (UFW).

Chávez served in the then segregated US Navy from 1944-’46. Upon discharge, he joined the Community Service Organization (CSO), a civil rights group in California’s Central Valley working to mobilize Latino voters and bring attention to the problems of police brutality and discriminatory immigration policies.

When the CSO refused to start organizing farm workers at Chávez’s insistence, he left the organization and used $1,200 in life savings to partner with CSO co-founder Dolores Huerta to launch the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) in 1962. In 1965, the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, an organization advocating for the rights of Filipino farm workers, asked the fledgling and largely Latino NFWA to join them in a strike against Central Valley grape growers over horrific working conditions and near slave wages.

Chávez put the proposal to a vote of NFWA members, who voted overwhelmingly to join the strike, which then became national in scope. Now known as the Delano Grape Strike and Boycott, it lasted five years and ended with a major victory for the farm workers. The final agreements produced significant improvements in their working conditions, safety and wages. The UFW union was born from the partnerships formed during the strike.

Although he never earned more than $5,000 a year and never owned a house or car, Chávez built a national coalition of students, middle class consumers, trade unionists, religious groups and ethnic minorities that saw Midwestern mothers finding common cause with migrant farm workers in California over the universal health risks of unregulated pesticide use on table grapes and lettuce.

Against seemingly insurmountable odds, and with a minuscule budget, Chávez led successful strikes, boycotts and marches that resulted in the first industry-wide labor contracts in the history of American agriculture.

Following the example of Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Chávez was a believer in the power of non-violent change and severely compromised his own health with repeated lengthy hunger strikes. His final hunger strike against supermarkets nationwide who refused to stop carrying and selling pesticide-laden produce picked by migrant farm laborers was called the Fast for Life. It lasted 36 days, ending August 21, 1988.

As he launched this fast, Chávez said.

“During the past few years I have been studying the plague of pesticides on our land and our food. The evil is far greater than even I had thought it to be; it threatens to choke out the life of our people and also the life system that supports us all. The solution to this deadly crisis will not be found in the arrogance of the powerful, but in solidarity with the weak and helpless. I pray to God that this fast will be a preparation for a multitude of simple deeds for justice. Carried out by men and women whose hearts are focused on the suffering of the poor and who yearn, with us, for a better world. Together, all things are possible.”

Not only can Chávez’s organizing efforts and fasts be considered a primary impetus behind the organic food movement of today, his actions brought about passage of the groundbreaking California Agricultural Labor Relations Act. (CALRA) Although it is under siege by the new Federalist Society Supreme Court majority, the CALRA remains the only law in the US that protects farm workers' rights to unionize.

FIGHTING FOR CLARITY

Chávez said, “I think one of the great, great problems is confusing people to the point where they become immobile.”

During this time of Covid, an unholy alliance of mainstream political actors, global financial interests, power hungry oligarchs and major corporate media have aligned in an effort to rescue the precarious global financial order upon which they depend for their power and privilege under the guise of protecting public health.

With no public mandate, they have also hijacked the pandemic to insist that official responses must focus on fighting climate change, now packaged as a “green and just recovery” from Covid-19 by groups ranging from the World Economic Forum to the United Nations and many others: Global Green New Deal, Natural Capital Coalition, Great Reset, Fourth Industrial Revolution, C40 Cities, Global Alliance for Vaccines & Immunizations, UN Climate Change Conference.

This elitist class cabal has become obsessed with preventing the consumption of Covid related “conspiracy theories” and “misinformation” by the great unwashed. Acting in their capacity as self-anointed “official” sources, they produce a deliberate onslaught of 24/7 state sanctioned propaganda, too often in the form of lurid fear-based narratives. Some social philosophers believe this has already led to a damaging “political economy of mass hysteria.”

The intent is not to inform, but to confuse and demoralize, to render people politically “immobile.”

Chávez biographer Miriam Pawel says that, “Fundamentally, his greatest accomplishment was empowering people who thought they had no power. To me, that’s very much his legacy, this idea that people can organize.”

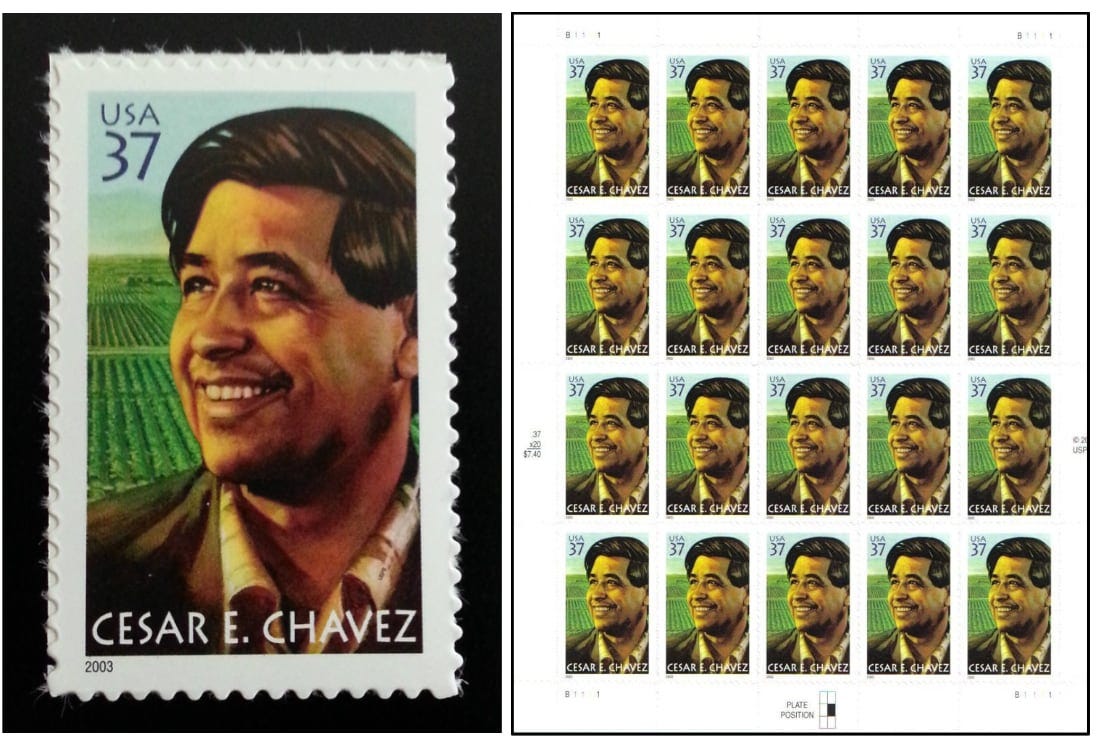

Today, this legacy has become institutionalized. In April, 2015, nearly 22 years after his death, Chávez received belated military honors from the US Navy. Former President Barack Obama issued a proclamation declaring March 31st to be National César Chávez Day. The US Postal Service sells César Chávez stamps. Schools, public buildings and a Navy ship bear his name. “Joe” Biden puts his statue in the Oval Office.

It is pointless to speculate what Chávez might think or do in the current pandemic with its noxious 24/7 plume of fear-based information smog. Yet in this toxic political milieu, the example of his clarity and simplicity in oppositional political organizing are worthy of being remembered and emulated. This includes his admonition to UFW members that “The more things people can find out for themselves, the more vigor the organization is going to have.” (Ibid.)

The now famous Chávez rallying cry ¡Sí se puede! (Yes you can!) coined by Dolores Huerta during his 25 day fast in 1972, has never been more powerful or relevant.