The gilded dysfunction of Versailles on the Potomac

The abandonment of citizenship fuels the rise of a reckless nuclear powered courtier class

“Liberty withers and decays unless it's put to use.'' – Lewis Lapham, The Wish for Kings

When asked to describe the transformation of the nation’s capital into a modern Court during a C-Span interview about his book, “The Wish for Kings,” author Lewis Lapham opined:

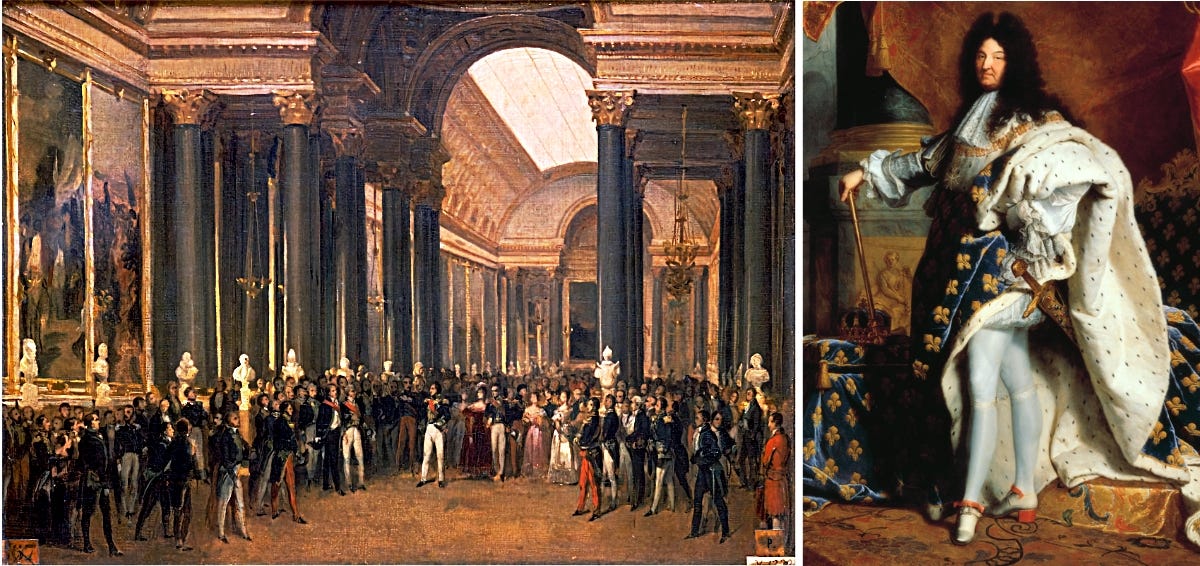

It's about the splendor of Washington that has been the magnificence of its marble, of its pretensions, of its bureaucratic vastness, so that it has become like a palace at Versailles. It is a court society, a world unto itself, sometimes called "inside-the-Beltway." It's grown and multiplied since the end of the Second World War so that the expense of government, the number of functionaries, of people who serve government in its many facets -- I think there's something like now 100,000 lawyers and lobbyists who work on various degrees of regulation. The staff of the Congress has multiplied to 35,000. It's this sense of a vast Versailles-like court, the Hall of Mirrors in which the various servants of government flatter one another or blame one another, strike poses, issue bills, make announcements, stage pageants of one kind or another.

Today, Mr. Lapham’s estimates of federal employment seem quaint, like the silver chamber pots that adorned the fragrant apartments of the original Versailles.

Projections for 2023 by the Congressional Research Service peg total Executive branch civilian employment at 2,288,566. Legislative branch employees are estimated at 35,240, and Judicial branch employees at 34,556. If the Post Office and uniformed military personnel are included, total US government employment for 2023 is expected to reach 4,339,753.

For comparison, Walmart, the largest civilian employer in the US, has only 1,300,000 domestic employees, about one fourth the federal government total. Amazon is number two with 1,000,000. Of the top 10 US employers, six offer primarily low wage positions in fast food or retail sales.

Thus as the splendor, wealth and spectacular nature of the government in Washington, DC grow every year, the ranks of the nation’s laborers are increasingly dominated by a low wage, low benefit peasantry whose only connection to political life is via voting in elections with pre-determined options guaranteed not to disrupt the affairs of the Court.

A MONARCHIST TALE FORETOLD

In 1835, in chapter XV of “Democracy in America,” in a section subtitled “The Courtier Spirit in the United States,” Alexis de Tocqueville already saw the ethos of the Court flourishing.

I have found true patriotism among the people, but never among the leaders of the people. This may be explained by analogy: despotism debases the oppressed much more than the oppressor: in absolute monarchies…the courtiers are invariably servile. It is true that American courtiers do not say "Sire," or "Your Majesty," a distinction without a difference. They are forever talking of the natural intelligence of the people whom they serve; they do not debate the question which of the virtues of their master is pre-eminently worthy of admiration, for they assure him that he possesses all the virtues without having acquired them, or without caring to acquire them; they do not give him their daughters and their wives to be raised at his pleasure to the rank of his concubines; but by sacrificing their opinions they prostitute themselves.

In a footnote in Chapter III, Tocqueville observes:

It is in the nature of all governments to seek constantly to enlarge their sphere of action, hence it is almost impossible that such a government should not ultimately succeed because it acts with a fixed principle and a constant will upon men whose position, ideas, and desires are constantly changing.

Today, three years of medicalized politics under the new Covid pandemic regime have facilitated a great upward consolidation of money (tens of trillions of dollars) and political power. With citizens literally muzzled and ordered to stay in their homes for nearly two full years, the ultimate triumph of the courtier ethos is nearly complete.

This was possible because the ideal of the engaged citizen had already atrophied to the point of endangered species well before Covid came along. The US has one of the lowest voter turnout rates in the world and more than one fifth of eligible citizens do not even register. This disengagement, coupled with the endlessly self-referential nihilism of courtier politics, has the world on the brink of nuclear self-destruction.

THE “ME” MILLENNIUM

In his famous essay in New York Magazine describing the 1970’s as the “Me Decade,” Tom Wolfe observed that radical political thinkers of yore often saw themselves as “engineers of the soul” whose principal role was to minister to the needs of a downtrodden working underclass.

Wolfe believed that this pattern had been radically disrupted by a massive post-World War II economic boom in the US that created an “…unprecedented American development: the luxury, enjoyed by so many millions of middling folk, of dwelling upon the self.”

In Wolfe’s formulation, the Me Decade was a challenge to “one of those assumptions of society that are so deep-rooted and ancient, they have no name—they are simply lived by. In this case: man’s age-old belief in serial immortality.”

Awakened to their own mortality, with “only one life to live,” and possessed of the kind of leisure time and money once reserved only for members of the Court at Versailles, the propelling ethos for large swaths of the post-War generation became self-indulgence, fueling a boom in global travel and the fulfilling of “bucket lists.”

In 2019, the last year before the pandemic, the UN reported that global tourism grew at a rate of 4%, greater than global economic growth of 2.8%, with 1.5 billion souls, nearly 20% of the world’s population, wandering the planet armed with selfie sticks and cell phones.

This was particularly alarming to old fashioned elites, people with real money and a deep seated belief in their own importance and power. Suddenly, the “Me Decade” had morphed into the “Me Millennium,” with grubby plebians in flip flops and bikinis invading once exclusive resorts in Mykonos, Paris, Prague, Ibiza and dozens of other exotic locations around the planet. Social media influencers, no matter how inane their associated commentary might be, even managed to monetize their invasion by gaining millions of “followers” for photo dispatches of themselves tramping around in the playgrounds of the rich.

With this new freedom of movement and the ability to monetize the kind of nomadic leisure lifestyle formerly enjoyed only by the ultra wealthy, the idea of the engaged citizen rooted in community took a major hit. Nomads are above all that. They’re “free,” unshackled from any particular place, usually without property, family, kids and the duties of citizenship.

Everyone is living for themselves. Serial immortality be damned when you’ve got 72 gender identities to choose from besides male and female. Lacking any kind of philosophic underpinning, the dominant credo before the Covid pandemic was consumerist pleasure. If it had an air of desperation, it was because the historical aberration of a large and relatively wealthy middle class was disappearing. The principal alternatives to nomadism had become low wage servitude in an Amazon warehouse or Walmart checkout counter.

A good pandemic, of course, has its uses. The travel restrictions and deeply personal intrusions of the Covid era once again emptied the luxurious retreats favored by the rich. The UN reported a stark 72% drop in 2021 tourist arrivals worldwide versus pre-pandemic levels. People were locked in their homes, forbidden to travel, forced to take injections whose efficacy and safety they might doubt. Suddenly, with the medicalization of authoritarian politics at a global level, the fun was over.

Pessimism has always been abhorrent to the Me Millennium’s sense of self because it implies limits. Amidst the narcissistic currents of the times, it has nonetheless enjoyed a resurgence among philosophers in recent years, perhaps because philosophic pessimism is not what people think. It isn’t Schopenhauer’s gloomy doomsday outlook nor the caterwauling of environmental doomsayers. It is simply a candid acknowledgment about the limits of what we can know and how far into the future we can see.

Such humility is not in fashion today. Everyone is all knowing, cocksure, self promoting. And it is difficult to imagine how that can end well. The entire point of modern capitalist “social” media is trivialization and performative self-degradation that creates malleable, easily manipulated subjects.

Engaged citizens animated by deeper enduring values and an elevated vision of both individual and social life are anathema to the new top down, elite driven feudal order.

In his C-Span interview, Lapham noted that “We're democrats to the extent that we try to tell each other what we know, what we've seen, what we feel. We're courtiers to the extent that we tell each other what each of us wants to hear.”

In today’s global electronic echo chamber, controlled by censorious multinational media corporations in service to imperial government, everyone is a courtier, but there are no more places at Court.