We don’t have Covid because we don’t believe in Covid

Dispatches from an alternative universe on Day of the Dead

“The Mexican...is familiar with death. He jokes about it, caresses it, sleeps with it, celebrates it. It is one of his favorite toys and his most steadfast love.” – Octavio Paz

To read the Spanish language version, click here.

Para leer la versión en Español clic aquí.

Since March 2020, official responses to Covid-19, inflamed by lurid 24/7 media fearmongering, have turned death into a kind of grim celebrity statistic used to frighten and intimidate people worldwide in order to implement what an Oxford University Press (OUP) report calls an “authoritarian pandemic.”

The OUP report notes that governments are using Covid and “science” as a pretext to systematically violate the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights, the American Convention on Human Rights, and the Arab Charter on Human Rights. This is happening as tens of trillions of dollars in “stimulus” are pumped into the failing corporate and financial sectors worldwide without comment.

At the same time, an enormously profitable and historically unprecedented new subscription model of vaccination requiring regular updates (boosters) like computer anti-virus software, is being implemented everywhere on earth, often by state mandate. This loss of democratic proportion and restraint, what the OUP report calls “unmistakable regressions into authoritarianism” in which fear of death is used as a daily instrument of state coercion, is a threat to civilization everywhere.

As this new globalized regime was being rolled out during the first year of Covid, a young Mexican filmmaker in the city of Oaxaca shared an incredible story with me over coffee one morning that flew in the face of what was happening elsewhere. He had just returned from a month long session teaching traditional photography and darkroom technique in a tiny indigenous pueblo in the mountains far outside the city. The people of the pueblo said they did not have Covid because, they did not believe in Covid.

This may not be very “scientific,” but it makes perfect sense psychologically. Bernard Henri Lévy has commented on the “psychotic delirium” created by Covid. This delirium is driven by a destructive and socially debilitating global obsession over the dangers of a virus that has both a very low Infection Fatality Rate (IFR) and high survival rate as well as a myriad of readily available preventive and early treatment protocols.

All statistics can be, and are, manipulated constantly, and globally sketchy Covid stats are even more of a minefield than other kinds of data. One can lose lifelong friends over numbers that bear almost no relation to the reality of daily life on either side of the discussion. Disagreements over Covid are religious. No one will ever “win” such arguments.

Yet the need to dig deeper for meaningful answers and broader context has an unexpected urgency as the connective tissue of civilization itself is riven, and possibly severed irrevocably, from its cultural and philosophic roots by the stresses of this pandemic.

Oaxaca and the annual Día de Muertos (Day of the Dead) fiesta offer a good starting point from which to explore alternative perspectives.

THE DIVERSITY OF LIFE (AND DEATH)

'“Can it really be said that before the day of our pretentious science, humanity was composed solely of imbeciles and the superstitious?” – R.A. Schwaller de Lubicz

The state of Oaxaca, México, which is larger than the nation of Portugal, has the greatest number of indigenous tribes in México. More than 16 officially recognized languages are spoken among 1.1 million indigenous people. Within the state’s 570 municipios, many of which have remained untouched for generations because of extreme mountainous geographic isolation, 176 linguistic variants are spoken, some tracing their roots to 4,400 BC.

The region is therefore home to a myriad of alternative political models with ancient roots, from Tequio to patriarchy and matriarchy. Modern parties and periodic elections staged to chose “representatives” have little agency in most of these communities.

Even contemporary debate over gender pronouns was foreshadowed and at least partly resolved in the 1500’s by the Zapotec people in Oaxaca’s Isthmus of Tehuantepec through the use of the now widely accepted sexual designation Muxes, México’s famous “third gender.”

My filmmaker friend said the people of the Covid-free pueblo, the majority of whom are college educated, govern themselves communally. Their goal is to protect the life-affirming integrity and political independence of the pueblo above all else because it is the pueblo that protects the individual members of the community.

DÍA DE MUERTOS

This story comes to mind because November 1, 2021, is the traditional Día de Muertos (Day of the Dead) holiday, one of the most beloved annual fiestas in México with special meaning across Latin America. Celebrations and elaborate public displays honoring the dead are in process from mid-October.

Although tourists who visit at this time of year love the colorful pageantry – parades, music, candlelit ceremonies in local cemeteries, displays in every building and public square and special Muertos food – it is not a holiday that is easy for non-Mexicans (and non-Latinos) to understand. Foreigners tend to think of it as harmless superstition or equate it with the ghoulish commercial pranksterism of Halloween in the West.

There is little knowledge outside México of Muertos’ pre-Hispanic roots tied to seasonal rhythms; its elaborate rituals and hierarchy for both the departed and living; the cyclical view of the universe at its core in which death is an integral, ever-present part of life; its myriad regional variations; nor the many ways, starting with the conquista, that the Catholic church has woven elements of this ancient cosmology into church holidays such as All Saints Day and All Souls Day.

Yet in Latin America, and especially in México, and in spite of the holiday’s inevitable and widespread commercialization by companies selling everything from beer to Starbucks coffee, Muertos has profound meaning for a large majority of Mexicans across differences of class and educational level.

Many of my Mexican friends spend hours painting their faces and transforming their bodies and clothing into works of art for Muertos every year. The painted faces are a modern replacement for the ritualistic masks that were worn in pre-Hispanic days (i.e., before Covid) to ward off evil spirits. This intricate facial painting often functions as an homage to a deceased loved one or as a life-affirming form of self-expression in the face of death.

DÍA DE MUERTOS SLIDESHOW

Click the image here to see a video slideshow featuring Día de Muertos photos shared by several dear friends, who are credited below.

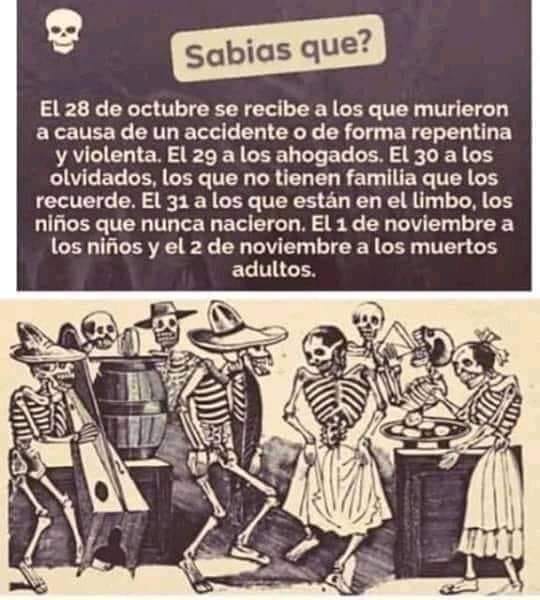

The Oaxacan friend who sent the illustration below noted the similarities between the levels of Dante’s Inferno and the structure of Día de Muertos according to type of death. But while Dante’s Euro-Christian model is punitive, the Día de Muertos tradition is capacious in its embrace – no one is forgotten, everyone is forgiven. Muertos is above all else egalitarian, a remembrance and celebration of and for the entire community.

Many friends over the years have shared moving stories about the holiday’s intimate personal significance in their lives: a grandfather’s spirit whispering secretly to a grandson; a daughter feeling the presence of her departed father more strongly every year; tales of boisterous annual family celebrations memorializing the life of a favorite fun-loving aunt or uncle.

Other friends feel strongly that Día de Muertos functions as an important annual reminder of life’s preciousness and contingency. How foolish we are to think that life will continue indefinitely when it could end this second, and how important it is to celebrate being alive in the moment while remembering those who went before us.

THE COVIDIZATION OF DÍA DE MUERTOS

In 2020, in-person celebrations of Día de Muertos were canceled nationwide in México and made virtual due to Covid, the long arm of the globalized national government attempting to reach into even the tiniest pueblos. There is great excitement about the “official” return of beloved Muertos celebrations in 2021.

This has not escaped the attention of the government. An 8.7 kilometer international parade with representatives from 23 nations is planned for October 31 in México City. According to Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum, the parade, which comes complete with “sanitary protections and checkpoints with random Covid tests,” is dedicated to the “thousands of people who have died from Covid-19 over the past year.”

Mexicans will make their own judgments about this international parade and the Covidization of Día de Muertos, but at minimum, the attempt to make Muertos a kind of global Covid brand is a stark reminder of how deep the social and political transformation of the past 19 months has been, and not because of a virus.

Humanity has confronted much worse problems without the kind of ongoing mass social, political and economic reconfiguration that has been taking place worldwide since March 2020 in the name of public health.

MY YEAR OF MUERTOS

My appreciation for Día de Muertos was forged in the crucible of a troubled year that saw the loss of three people I loved in the span of 11 months, culminating with my own hospitalization in the twelfth month.

KARIN

On April 1, 2018, I received my final text message from Karin, a beautiful 30 year old friend who was in hospital in México City with a fatal disease. The message, in response to a photo I had sent from Los Angeles, was simply a heart emoji. She died a few days later.

Every conversation that Karin and I ever had was nearly febrile with excitement and emotion. She was a beautiful soul, and we talked endlessly about life’s beauty and strangeness, the importance of love and joyful living. One of our last conversations, before the disease overwhelmed her, was about our own experiences with romantic love. It became very emotional, and I remember clasping her long elegant fingers in my hands as she cried with a mix of joy, past loss and future possibilities.

HOLGER

Less than two weeks later, the body of my friend Holger was found in a ravine in the remote mountains of Chiapas, México, where he had been en route to the Yucatán via bicycle to visit a mutual friend. He had been murdered, a single bullet through the head. Because I reported Holger missing to the German embassy, I became involved with his family working to recover his body and ended up traveling to Germany for his moving memorial service in August. It was an intense four months.

The day that Holger and I were introduced by mutual friends in Puerto Vallarta, I wrote that he was one of the happiest people I had ever known. The connection was immediate and strong, the loss devastating. I’ve written about the remarkable sense of adventure and wonder that informed Holger’s life in both English and Spanish.

PEGGY JOYCE MEURER

A few months later, in December 2018, I learned that my mother had been put in a home for people with Alzheimer’s disease. I did not believe she had Alzheimer’s and flew to the US, where, with the help of my niece, I spent the next six weeks trying unsuccessfully to enlist social services and the police to get her released. I returned to México in January with investigations ongoing.

My nearly 99 year old mother, one of the strongest people I have ever known, died on March 18, 2019.

ONE FROM THE HEART

The next month, April 15, 2019, one year after Karin’s death, I had a heart attack and underwent emergency surgery in México City. Recovery has been a long and winding road. But even with a mountain of debt after many hospitalizations, I’m back walking two miles per day, more aware than ever that every moment in which one is able to fully enjoy life is a gift.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE DEAD

German sociologist Norbert Elias famously said, “Death is the problem of the living. Dead people have no problems.”

Yet in spite of, or perhaps because of, its inevitability, humans often find awareness of death unbearable. “It is therefore a…continuous task for the living to try to deal with death. Culture itself…is intended to make such a life with death bearable and livable.”

Día de Muertos is a cultural adaptation in which the living come together to confront individual mortality within a larger, shared social context. I find it’s mix of celebration and joyful remembrance to be profoundly meaningful as an antidote to irrational fear.

The love, laughter and celebration of Día de Muertos leavens sadness and serves to remind us that “the lives of the dead are complete, free from the sway of Time. In the quiet country of the past, the tired wanderers rest, and all their weeping is hushed.”

We cannot continue to punish the living out of fear of death. It has deranged our lives and our politics. Humanity is still capable of rejecting this lethal cocktail of fear and division. Civilization depends upon our doing so.

The great French philosopher Gaston Bachelard cautioned that science itself must stay vigilant not to impede “scientific imagination” by succumbing to “the seduction of the empirical.” He noted that as humans, our fate is to live in “moral time” in which the goal is “to make poetry and science complementary, to unite them as well defined opposites.”

The challenge of our time is to carry on this work together with calm, strength, vision and courage, embracing and building upon the lessons and sacrifices of our dead forebears without succumbing to fear, despair and negation.

IMAGES: Skull photos by Michael, Día de Muertos illustration courtesy of my friend Armando. Photos used in the slideshow are courtesy of my dear friends María, Fernanda, Armando, Mari, Mariana and Diana. Many thanks to all of you.

SPANISH LANGUAGE VERSION

The Spanish language version of the article can be read here.